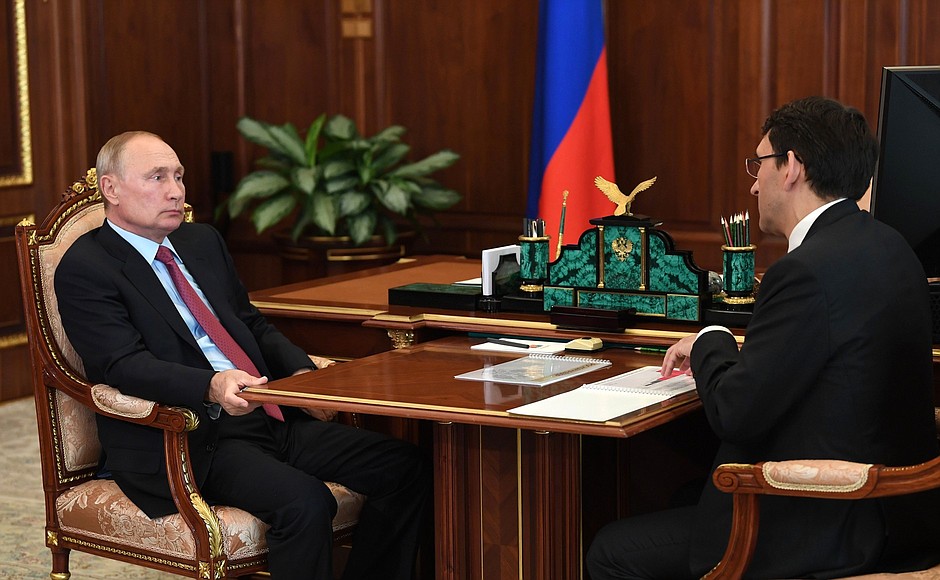

President of Russia Vladimir Putin: Good afternoon. Roskomnadzor is a multidivisional agency with a broad network. How many branches does it have, over 70?

Head of the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media Andrei Lipov: Seventy-one.

Vladimir Putin: This is large-scale. We are all talking, and not just talking but taking major steps to digitise our economy, life in general and the social sphere. Therefore, of course, protection of personal data is a particularly topical issue. Could you begin your report with this?

The law envisages nine types of administrative offences relating to the violation of Russian citizens’ rights. How is the agency addressing this area of work?

Andrei Lipov: Thank you very much.

I can tell you that, with the abundance of online services that have appeared, the digitalisation that we need always involves personal data processing, which creates a great many problems.

Vladimir Putin: There are also many private companies dealing with personal data, is that correct?

Andrei Lipov: Yes, private companies are in the majority. We estimate that there are almost five million personal data operators. It is a significant number considering that they require supervision.

There have been many complaints. We received some 43,000 complaints from the public last year, which is a 20-percent increase year-on-year. Many issues occur due to our underdeveloped laws.

I have a number of proposals that could change the situation for the better. If we take, for example, penalties, the biggest fine charged for personal data leakage or, to be more precise, for the unlawful use of personal data, amounts to 75,000 rubles. This fine is incommensurate with the perpetrator’s profit and with the damage arising from such processing.

Vladimir Putin: You mean damage caused to an individual.

Andrei Lipov: Yes, damage to members of the public.

For some reason, the statute of limitations is very short. We would like to extend it to one year because in some cases, the statute of limitations expires before they get to court.

Roskomnadzor is authorised to inspect, but very often we can see when checking that the data is transferred to the next processor for processing and then to the one after that, and we do not have any legitimate authority to inspect the entire chain. Here, too, I would like to improve the situation.

The next question is how they actually process personal data. As of today, all we can do is so-called documentary control, that is, we can inspect their documents to see which internal documents regulate the way they process users’ personal data, and how well these documents comply with the legislation, Federal Law No.152. But we have no way of seeing how they actually process personal data.

Maybe it would be a good idea for us to think together with the legislators about authorising instrumental control. If we had this, we would be able to build a technological appraisal system so we could check, in case of any doubt, how legitimate their personal data processing practices are. We need to know if the purpose corresponds to the way the data is processed, and the timeframe, and a number of other factors.

An important aspect of personal data processing is the cross-border nature of such data, of course. The European Court of Justice decided to terminate the so-called Privacy Shield – an EU-US agreement on Europeans’ personal data processing in the United States. Everything was fine until the European Court decided that Europeans’ data was not being properly processed abroad. Now experts believe that, with this agreement terminated, US companies will have to move their servers to Europe, so as not to violate European legislation. We will see what comes of it.

In general, under Convention 108 for the Protection of Individuals with regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data (it was updated not so long ago; we joined it and were actively involved in the changes), a state has the right to determine other countries that do not provide for due processing of personal data. We would like Roskomnadzor to take up this responsibility. Let us assume that my personal data was leaked online and considered public data. Many people do not deserve this kind of treatment because currently it is not so easy to close a fake account of some public figure. They say, “Check your law – this is public data.”

We would like to develop a mechanism that would allow a person to say, “Sorry, even if I am a public figure, information about my leisure time has nothing to do with information of social, political or public significance.” This would allow the person concerned to have information that has been misused deleted by going to court.

Of course, there is a risk that courts of different levels will issue too many orders on removing information about people who perhaps do not deserve the negative information about them to be deleted. And this is something that probably requires thorough research. Last year, we received 58,000 court orders regarding various offences (not only concerning personal data). Fifty-eight thousand is a big number. We are afraid that the number of these orders will continue to grow and we might throw the baby out with the bathwater, so to speak. There should be a way for the people who truly do not deserve such treatment to be able to have insignificant information about themselves removed at least through the courts.

Processing biometrics is an important aspect. There is a huge number of systems based on biometric data. Unfortunately, personal biometric data are the data that we can give up only once in our lives – that is, at the end of life. It is something that we cannot change at all. Other personal data such as passport data and the passport itself may be replaced but not our biometrics. At the same time, we do not yet know all the consequences of biometric data processing. For example, a person’s iris contains information about all the diseases a person has. When it comes to retinal identification, we do not know yet how this data could eventually be used without its owner’s knowledge.

All told, we would like to think about clearer regulation in this area, and more careful too. Naturally, we do not want this regulation to somehow infringe on the goals for the development of the digital economy that we have.

This covers the work scope facing us in terms of personal data matters.

Vladimir Putin: Fine, we will discuss this now. Anything else?

Andrei Lipov: I would like to tell you more about illegal information in general. Since 2012, when legislation was first adopted to remove prohibited content from online resources, more than 1.5 million materials have been removed.

Vladimir Putin: What kind of content, exactly?

Andrei Lipov: Speaking of last year, we saw significant growth. Over the past year, in 2019 alone, 531,000 such materials, mainly stipulated in the 2012 legislation, had to do with advocating suicide, child pornography (alas, there is a lot of it) and information concerning the distribution and promotion of drugs. But out of the 531,000 that I mentioned, 208,000 concerned extremist and terrorist organisations. This is a huge proportion and the main challenge today, I would say, in terms of addressing prohibited content on the internet.

For the most part, Roskomnadzor catches all those threats. Almost 800 people are working in our round-the-clock service in all constituent entities of the Russian Federation, and in all time zones. As many as 9,500 conventional media outlets, about 500 television and radio channels and all the most popular social media platforms are constantly on our radar.

It is clear that the main problem we have is the internet, because media consumption has largely shifted online, and this is where the main challenges are. Because traditional media, although there are a lot of such outlets, in total about 66,000, I think, but the share is slightly decreasing – down 9 percent over the past year, I think, but on the other hand, the growth in internet traffic has been enormous, which shows it is actually where people mostly get their information. We have seen a 50 percent increase in mobile traffic over the past year, which is quite a lot, and 20 percent in fixed-line communication. In absolute terms, fixed-line traffic is still three times higher than the mobile option, but the growth is quite high because people are spending more and more time online via mobile phones.

The main challenge is a shift in the use of internet content. Personal data are also a basic challenge, but the growth of this internet traffic also puts a load on communications networks. If you take these three aspects, as I have already said, there were 43,000 complaints about personal data last year, up 20 percent. Complaints on the negative content that users see on the internet is also up 20 percent, but this amounts to 557,000, which is significantly more; I am referring to complaints about negative content. This is a lot. In other words, people see the negative content themselves and complain, and we analyse it through this monitoring group.

Every year, the number of complaints about communications services is not very high. It does not change much and stands at about 29,000 or 28,800 to be precise. But there was a spike during the pandemic. During the four months of quarantine when people had to sit at home, of course, the increase in complaints about the quality of communications services went up by 49 percent.

Vladimir Putin: The networks were overloaded.

Andrei Lipov: The networks were overloaded. Not all communications operators had the same amount of reserve capacity. Regrettably, some communications operators had a load of 80–90 percent. In other words, if a bit more people had been at home, these networks would have been unable to cope with the situation. This is true of many operators, although not of all of them.

Probably, it is necessary to find an option when we and the communications operators in the regions have the opportunity to determine priorities in the development of communications networks in order to get a bit ahead of this situation. Seasoned communications operators say that in normal mode the network should not have a load of more than 30 percent in order to cope with a threefold load.

I have already mentioned the main challenges. What will we do this year to cope with them? First of all, we must create an information system, that is, develop the information system on monitoring the internet. There is still a lot of manual labour to do. The monitoring system is automated. It reveals an issue, and people check on it. We would like to reduce the amount of manual labour, increase the speed and, certainly, the coverage. For this purpose, we will use new digital technology, and try to apply neuronets. We hope to increase the precision of the search for illegal information to 85 percent.

<…>